When I first heard the term urban ecology, it conjured images of the trees, plants, and wildlife that we see in an urban environment. While that certainly is one definition, I am more excited about another meaning of urban ecology: “the study of cities as urban ecological systems” (ix, Grove et al, 2015). To me, this field of study reminds me that we are inherently connected to our natural environment and that our built environment (i.e. our cities, roads, buildings, etc.) is driven in part by the same rules and processes that govern our natural environment.

Image displaying a city blended with a leaf. Hofstra University

The implications of this in city planning are immense. As the Baltimore School of Ecology discusses, “scientific curiosity, social- ecological system complexity, and the multifaceted nature of sustainability and resilience— require new approaches for studying the city: its regions, global connections, and internal changes” (Grove, 2015, pg. xii)

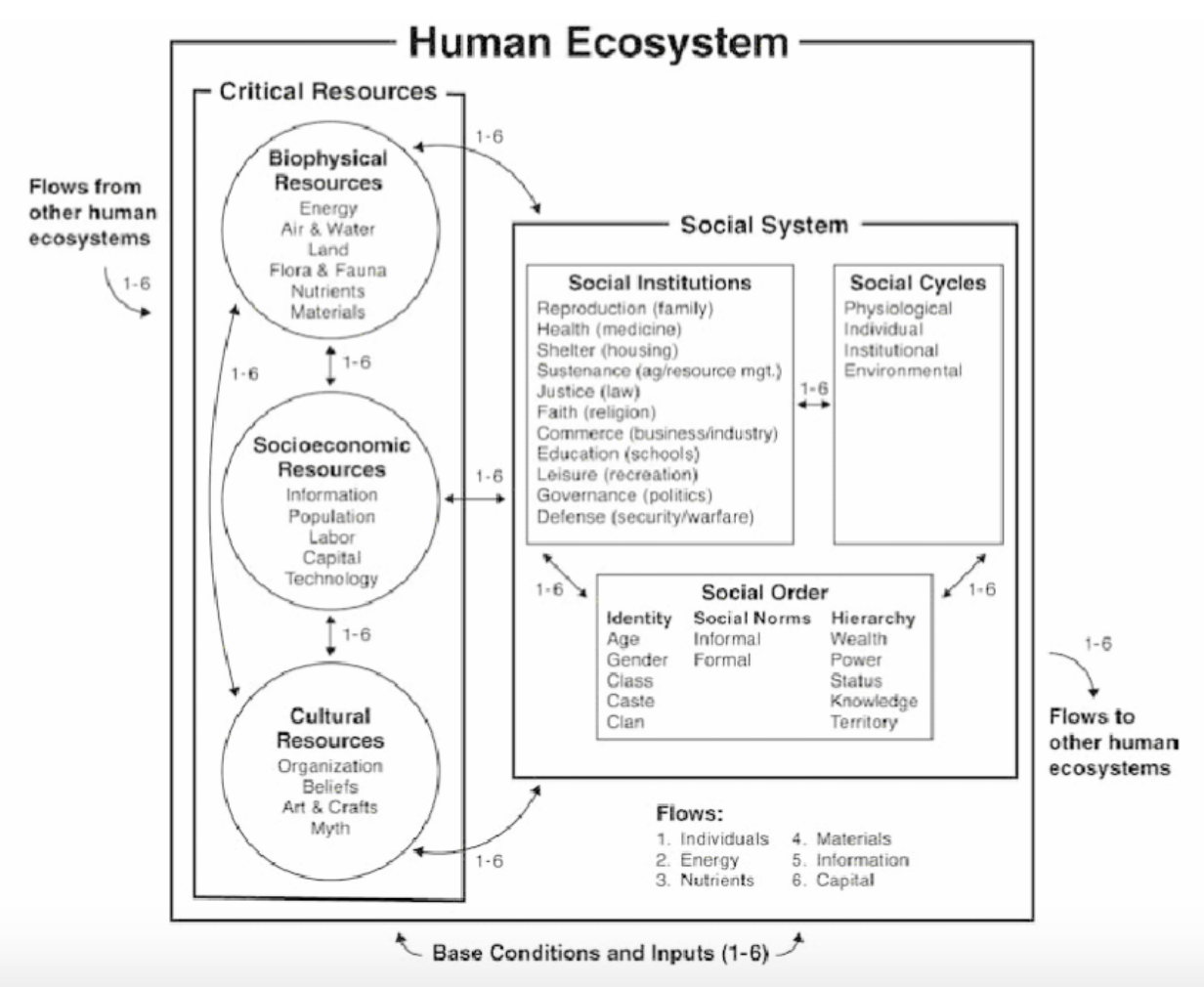

Diagram visualizing the human ecosystem. (Grove et al, 2015, pg. 8)

While cities have historically been seen as counter to the goals of environmentalism, current scholarship and work within urban ecology studies highlight how cities and sustainability goals are intertwined. For example, cities offer, “efficiencies of scale, savings in energy and materials, and benefits of innovation and interaction that accrue to urban systems” (Grove, 2015, pg. xiv).

Urban ecology is an interdisciplinary field that can inform decision-making and city planning needed for healthy, sustainable, and equitable cities. I would like to explore some examples of urban ecology as it relates to our cities today.

Legacy

The choices that we make today will impact our communities far into the future. Understanding the present impacts of past decisions will help us make more equitable decisions moving forward. As the Baltimore School of Urban Ecology describes, “the historical distribution of physical environmental conditions, soils, and biota can influence contemporary and future ecological and social conditions. The built environment is itself a legacy in many urban systems” (Grove, 2015, pg. 6).

Diagram showing the multidisciplinary nature of Urban Ecology: complexity, urban planning, governance, urban design, ecology in cities, social sciences, stewardship, systems thinking (McPhearson et al, 2016, Figure 4)

This includes physical legacies, such as road systems and names, parks, and neighborhood demarcation. This also includes social legacies, such as the redlining and rezoning that segregated neighborhoods across the country (Rothstein, 2017). Decisions that were made many years ago have real consequences in the present. We need to learn to recognize these legacies and work towards sustainable, resilient, and equitable solutions.

Urban Resilience

We need a shift in our cities to build urban resilience, especially in light of gentrification and displacement, impacts of a changing climate on our communities, and the ongoing impacts of COVID-19. The pandemic has highlighted many of the flaws in our current city systems. As Niemela et. al. explain in their book, Urban Ecology: Patterns, Processes, and Applications, “Just-in-time production/distribution systems, small government, and even cost-effective nonprofits are driving forces of our competitive, globalizing world. A strong argument for ‘investing’ additional resources in building resilience is that in the ‘long-term’ these costs are well justified” (Niemela et al, 2015, pg. 212).

Diagram outlining 5 elements of urban resilience: urban governance, resilient infrastructure and basic services, urban disaster risk management, urban planning and environment, urban economy and society (DiMSUR CityRAP Tool).

In other words, the study and practice of urban ecology can help us build more sustainable and resilient systems. I believe the more we understand about how our systems work, and how systems in our surrounding biological ecosystems work, the more we can come up with creative solutions that build resilience equitably.

I think if we connect more deeply to place, look to the past, and explore our current built environments with a lens of ecology, we can better understand our current solutions and work towards solutions that get at the root causes of injustice. This will take a shift in perspective for all of us. What would it look like for us to shift our perspective to our surroundings, to understand the past of our neighborhoods and cities, to broaden our understanding of our place within it, and to envision various futures for our built environment?

Sources:

Grove, J. Morgan, et al. The Baltimore School of Urban Ecology: Space, Scale, and Time for the Study of Cities, Yale University Press, 2015. ProQuest Ebook Central, http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/ucb/detail.action?docID=4093126.

McPhearson, T., Pickett, S., Grimm, N., Niemelä, J., Alberti, M., Elmqvist, T., Weber, C., Haase, D., Breuste, J., & Qureshi, S. (2016). Advancing Urban Ecology toward a Science of Cities. BioScience, 66, 198-212.

Rothstein, R. The Color of Law: A forgotten history of how our government segregated America. Liveright Publishing Corporation, 2017.

Urban Ecology: Patterns, Processes, and Applications, edited by Jari Niemelä, et al., Oxford University Press, Incorporated, 2011. ProQuest Ebook Central, http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/ucb/detail.action?docID=800872.