Welcome back to the Our City Forest blog. Today we have a guest post by one of our Americorps volunteers, Chad Machinski. As one of the growers at the nursery, Chad is responsible for cultivating and raising the trees that we provide to the communities of the Silicon Valley. He's a massive plant enthusiast and an awesome guy. I hope you enjoy his post.

The sun filters diffuse and low through the fog of the redwood forest. The air is cool. Moss and ferns dampen your footfalls in the near-silence. A salamander, dark with light gray dapples leaps from a fern to a nearby tree trunk, scurrying into a moist crevice. The fuzzy face of a pine marten stares at you from a nearby branch and in the tree-muffled stillness you hear the hoot of a spotted owl. The scent of a bay laurel wafts on a light breeze. You adjust your belay harness and keep climbing. You’ve entered the epiphyte community of the redwood rainforest, a forest-within-the-forest one hundred feet in the air.

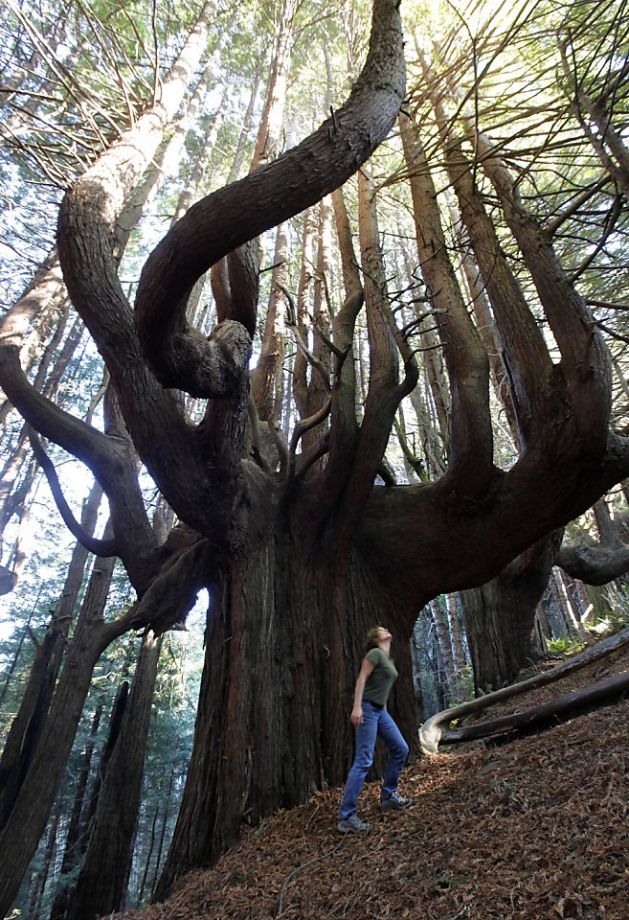

Redwoods can develop complex structure, providing additional canopy habitat. (Source)

‘Epiphyte’(“epi” = on top of; “phyte”= plant in Greek), is a fancy-sounding term for a plant that spends most or all of its life living on another plant, usually on a tree . You might think that an epiphyte is a parasitic plant, but it is not! These plants only use the tree as a support system and take no nutrients from the tree itself. They instead rely on rainwater to carry nutrients down tree bark or on collections of soil and detritus in the crotches of branches. Epiphytic plants are represented throughout the plant kingdom, including non-vascular plants (mosses, liverworts, hornworts) and vascular plants (plants that can conduct water).

While South and Central American rainforests are epiphyte hotspots, there are some that grow in the North American temperate rainforests. Here in California, the coast redwood (Sequia sempervirens) is a fantastic host of epiphytic plants due to its large canopy with crotches in the tree and large canopy branches. The most common vascular epiphyte on the coast redwood is the leather-leaf fern, (Polypodium scouleri). Studies have found mats of leather-leaf fern that had estimated weights of up to 11 lbs. Soil and detritus found in many tree crotches and among the mats of leather-leaf fern is probably generated by the fern itself in a self-perpetuating, habitat-building cycle. These soil layers can be up to a three feet thick with the volume of a small school bus. Water retained by this decaying material allows many terrestrial organisms to live in the coast redwood canopy. In addition to ferns, there are actually shrubs such as gooseberry (Ribes), Pacific coast red elderberry (Sambucus callicarpa), and blueberry (Vaccinium) share in the epiphytic glory. Redwoods are so large that other trees can be found growing on them as epiphytes. Some of the trees that have been documented growing on the coast redwood include cascara (Rhamnus purshiana), sitka spruce (Picea sitchensis), Douglas fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii), western hemlock (Tsuga heterophylla), and California bay laurel (Umbellaria californica).

The wandering salamander another arboreal salamander found in redwoods (source)

These plants in turn all allow terrestrial animals to occupy the redwood canopy. Leaping, prehensile-tailed cloud salamanders (Aneides ferreus) make their homes in fern mats. Peregrine falcons (Falco perigrinus) bald eagles, (Haliatus leucocephalus) and northern spotted owl (Strix occedentalis curina) make their nests among the forest-within-the forest along with egrets and many, many species of bats. Pine martens (Martes americana) raccoons (Procyon lotor) and flying squirrel (Glaucomys sabrinus) make their homes in the canopy. There is a whole ecosystem in the branches above our heads as we walk through the redwoods.

Forestry practices have greatly changed the abundances of epiphytic communities. Old growth forests represent what the epiphytic communities probably looked like prior to logging and containing hundreds of species. Logging has reduced the epiphyte-harboring old growth forests to approximately 4% of their original range.New forestry practices can recreate old growth-like characteristics of trees that are favorable for the development of epiphytes. The downside is that secondary-growth trees are less likely to reach the size that can support large fern mats, thus reducing the available habitat in the canopy. Compounding this problem is the local loss of species in formerly clear-cut forests. Without wildlife corridors from old growth redwood to managed secondary growth forests it is difficult for epiphytes to recolonize formerly-cleared ranges.

Other trees besides the Coast Redwood can also be hosts for epiphytes. The sitka spruce, itself a potential epiphyte, can host epiphytes of its own. The largest plants that have been found growing epiphytically on sitka are ferns, while the majority of the epiphytes are smaller, non-vascular plants such as lichens, mosses and liverworts. I personally (and probably you as well) have also seen mosses and lichens growing on plenty of trees besides the two mentioned here and hope that future research will shine a light upon those other trees and their epiphytic communities.

As important as other epiphyte communities are, the redwood epiphyte community dwarfs all North American competitors in terms of diversity and complexity. The forest within the canopy increases the biodiversity of the redwood forest, the density of available habitat and challenges certain assumptions we have when it comes to managing the forest. If we are to maintain the biodiversity of redwood forests we need to take the epiphyte community into consideration. We also need to modify our approach to studying the community to better understand the forest within the canopy, 100+ feet above the ground. California is proud of the redwoods and should be doubly proud of their unique epiphyte communities.