What is a plant community?

In Ecology, a community is one of the various levels of ecological organization. These levels of ecological systems are used “to better understand the frame of reference in which they are being studied” (MSU). In other words, it helps ecologists define the scope of their studies and observations. These levels start at an individual of a species then climbs upward to species population, community, ecosystem, and biosphere. The community level is composed of multiple species that share a common environment. An ecosystem, on the other hand, includes both living organisms and nonliving features such as minerals and water. A plant community refers more specifically to plant species that grow in shared environments and in relation to each other. However, plant communities, and ecological communities more broadly, are not discrete zones that have definite and defined boundaries. Plants found in one community can be found in others and communities transition into others. Chaparral spills into oak woodlands and oak woodlands blend into redwood forests.

Serpentine Chaparral overlooking San Francisco (Image source)

The California Floristic Province and Mediterranean Climates

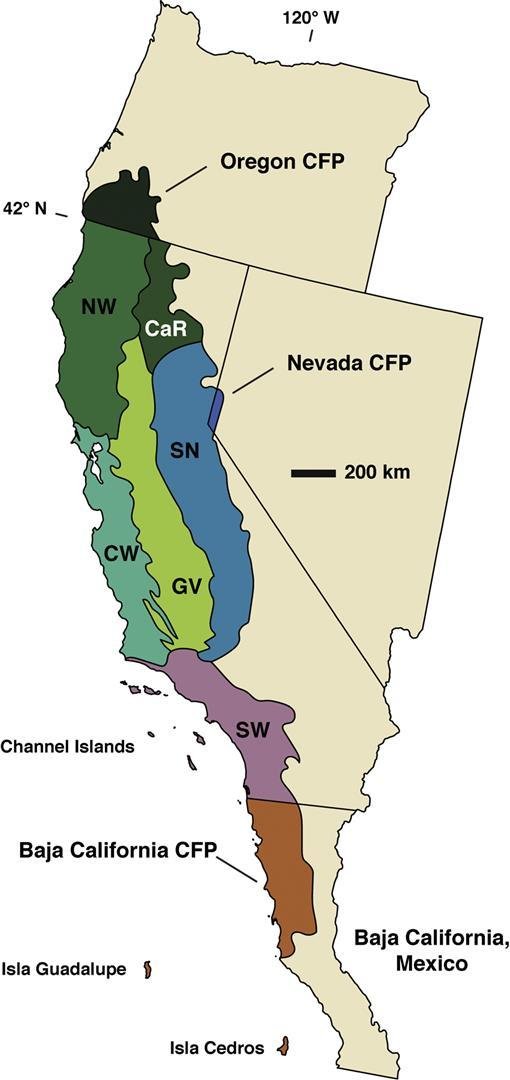

Santa Clara County is part of the California Floristic Province, a biodiversity hotspot that ranges from Baja California up to Southern Oregon, including the coastal islands along that range including the Channel Islands.

This region of biodiversity is defined by a Mediterranean Climate. This type of climate is considered to be globally rare and found only in 5 regions in the world: California, Central Chile, the Western Cape region of South Africa, South West and Southern Australia, and the Mediterranean basin (which includes North Africa, parts of Europe, Western Asia, and parts of the Middle East). This climate type is characterized by hot, dry summers and wet, cool winters which is reflective of Santa Clara County’s hills, which become a brilliant emerald in winter and golden in the summer. Many non-native, drought-tolerant species of trees and shrubs found in Santa Clara County are native to other Mediterranean climates such as rosemary, lavender, African fern pine, etc. Unfortunately, some of these plants are highly invasive (such as mustard, broom, and eucalyptus) and out-compete native species that our native ecosystems depend on.

Plant Communities of Santa Clara County

Santa Clara County is highly diverse with many microclimates that allow for certain plants to thrive in specific areas.

CHAPARRAL

Chaparral is dense shrubland characterized by diverse drought-tolerant, woody shrubs. The California Chaparral Institute lists 13 different types of chaparral in California alone and notes of other international chaparral communities from other Mediterranean climates. Among these California types are Serpentine chaparral, Desert chaparral, Ceanothus chaparral, and Island chaparral.

Species found in Santa Clara County

Chaparral Currant (Ribes malvaceum) is a member of the Gooseberry family. This beautiful shrub with pink, tassel-like flowers and round, pink berries is one of our most popular shrubs that Our City Forest plants in our Lawn Busters program.

Hairy Ceanothus (Ceanothus oliganthus var. oliganthus), commonly called California Lilac, is a wildfire resilient shrub. Its dark leaves contrast beautifully with seasonal blooms of periwinkle flowers. Ceanothus is another popular drought-tolerant shrub that we use in our Lawn Busters program and they come in a large variety of species and cultivars.

GRASSLAND

Serpentine Grasslands at Calero County Park (image source)

Grasslands in Santa Clara County include Serpentine Grasslands, Annual Grasslands, and Non-Native Grasslands. Serpentine Grasslands are perhaps the most interesting. This type is defined by serpentine soil, which is high in serpentinite, a stunning banded green rock. It is also California’s State rock! Because of serpentine soil’s unique balance of calcium and magnesium, non-native plants tend to not survive in these soils, leaving room for native plants to flourish.

Species found in Santa Clara County

Purple needlegrass (Stipa pulchra) is California’s State Grass and most widespread native grass. It is perennial and evergreen and attracts many bird species from the large amount of purple seeds that it produces.

Ithuriel’s Spear (Triteleia laxa) is an herbaceous perennial wildflower in the Lily family. The name Ithuriel comes from a character in John Milton’s epic poem, Paradise Lost, who reveals a toad to be Satan’s by pricking him with a spear (USDA).

OAK WOODLAND

Oak woodlands at Coyote Lake - Harvey Bear Ranch County Park (image source)

The eastern hills of Santa Clara County are rolling hills bespeckled with the dark green foliage of oak trees. These hills are generally drier than their western counterpart, the Santa Cruz mountains which tower with misty Coast Redwoods. The Oak Woodland plant community is generally dry, especially in the summer, and intermingles with other communities like grasslands and chaparral.

Species found in Santa Clara County

Coast Live Oak (Quercus agrifolia) is a keystone species, meaning that it supports the survival of hundreds of other species. This species in particular, according to Calscape, supports a total of 270 species. It is also highly fire resistant and old growth trees can survive being scorched.

Toyon (Heteromeles arbutifolia) gave Hollywood its name. Settlers who came to California thought it to be a type of holly berry! Toyon is another fire resistant species and commonly likes to grow as a companion to Coast Live Oaks. While Toyon is technically a shrub, it can be pruned into a tree. Birds love their red winter berries which are also edible for humans when cooked.

RIPARIAN

Coyote Creek is a critical wildlife corridor in Santa Clara County (image source)

Riparian habitat exists in the transition between terrestrial and aquatic environments. This plant community is dense and rich with shrubs, grasses, and trees. These plants must be adapted to tolerate seasonal floods from California’s winter rain storms whereas plants specifically adapted to drier environments can be very intolerant of excess water. Riparian habitats are important wildlife corridors that allow animals such as bobcats, deer, and coyotes to move across the landscape safely.

Species found in Santa Clara County

Blue Elderberry (Sambucus cerulea / Sambucus mexicana) is a gorgeous shrub that can also be pruned into a tree. Its delicate parasol-shaped clusters of flowers turn into dusty blue berries that a variety of wildlife depend on. Both the flowers and berries are edible and have medicinal uses. However, the berries are toxic to humans unless they are ripe and cooked. There are four types of Elder in California (and more internationally), but only Blue Elderberry grows naturally in Santa Clara County.

California Mugwort (Artemisia douglasiana) is an edible, aromatic, and medicinal herb often found along creek sides. Some California Indigenous tribes, such as the Chumash and Paiute, used mugwort to nurture sacred dreams. If you come across this towering herb, gently rub a leaf between your fingers to release its medicinal aroma.

CONIFEROUS FOREST

Mt. Madonna County Park (image source)

Conifer trees are cone-bearing trees such as redwoods, firs, and pines. Santa Clara County is bordered from the South and South-West by the Santa Cruz mountains that maintain their deep forest-green foliage year-round. Many plant species live in the shady Redwood understory including other coniferous species. The Santa Cruz mountains are the primary place in Santa Clara County where Redwoods naturally occur. Throughout San Jose and bordering towns, Redwoods have been planted at lower elevations in an urban setting. However, these Redwoods tend to live stressed lives from that lack of fog that they have evolved to live with.

Species found in Santa Clara County

Coast Redwood (Sequoia sempervirens) is the tallest tree species. The tallest known living tree is a Coast Redwood named Hyperion, standing 379 ft tall. This tree’s exact location is undisclosed but lived approximately in Northern California close to Oregon. Hyperion is estimated to be 600-800 years old, but Coast Redwoods can live up to 2,200 years old.

The Pacific Madrone (Arbutus menziesii) is an evergreen tree that lives in the understory of Coat Redwoods but can also be found in oak woodlands. Like its cousins the manzanitas, the Pacific Madrone has reddish orange bark that peels away as it ages. Its flowers are shaped like clusters of delicate, white bells that flower in the spring.

WETLAND

The EPA defines wetlands as “areas where water covers the soil, or is present either at or near the surface of the soil all year or for varying periods of time during the year, including during the growing season”. This broad definition means that wetlands are incredibly biodiverse! The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) divides wetlands into 5 types: marine (ocean), estuarine (estuary), riverine (river), lacustrine (lake), and palustrine (marsh). These categories include both saltwater and freshwater environments, as well as brackish (a mix between freshwater and saltwater found in areas like estuaries where the salinity levels fluctuate). Read more about Wetlands in our World Wetlands Day 2024 blog post!

Species found in Santa Clara County

Tule or Hardstem Bulrush (Schoenoplectus acutus) is a large freshwater grass that grows throughout California wetlands. Indigenous groups across California use tule to make houses, clothing, mats, baskets, and tools.

Saltmarsh Baccharis (Baccharis glutinosa) is a flowering perennial herb that grows in saltwater marshes. This plant grows through rhizomes, a specialized stem that grows underground (not a root!). These rhizomes spread underground where new stems and leaves can pop up away from the original plant.