Part 1: What is an oak tree?

Oak trees belong to the genus Quercus meaning “fine tree” in Latin. They are native to the northern hemisphere and consist of some 600 species. Oak trees are unique because of their fruit, the acorn, which is key in identifying oak species. They are known for being multi-trunked and growing wide canopies with sprawling, scraggly branches.

Part 2: A (Brief) History of Oaks In California

The history of oaks in California is long and storied. Oaks have long had a place in Californian culture. We celebrate these trees that once covered a third of the land in the names of our cities, towns, and schools (think Oakland, Encino, Paso Robles, Live Oak High School...the list goes on). The native oaks of California once dominated the landscape. Accounts of Spanish explorers mention their awe at the sight of the abundance of oaks around them. However, those with the strongest connection to the oaks of California were and are indigenous people.

Map of the Ohlone peoples and their neighbors

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ohlone

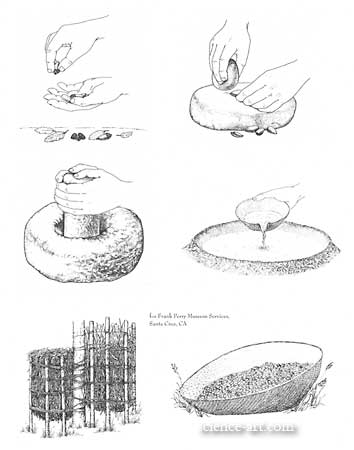

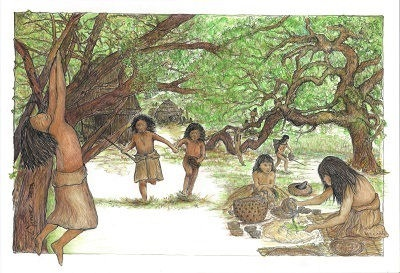

The people native to Santa Clara Valley are known as the Ohlone, which is a name that encompasses 50 separate tribes ranging from the South Bay all the way down to Monterey. Native oaks of California are ingrained in their society as a resource both physically and spiritually. Acorns were the primary food source for the Ohlone prior to the arrival of the Spanish and were held in high regard amongst the native people. Anthropologists estimate 75% of native Californians relied on acorns in their daily diet. Their new year, a joyous occasion, was marked by the acorn harvest. The Ohlone people would dance amongst the oak groves each year to promote a good harvest. During the acorn harvest, entire families would go out and collect the acorns of a large tree, which took about a day. The women would then prepare the acorns by shelling them and using a mortar and pestle, grinding the acorns into a fine powder. After being ground, the acorn flour would undergo the lengthy process of leaching the bitter tannins from the acorns which made them unpalatable. After the tannins were leached, the acorn flour was much sweeter and easier to eat and could be used to make soups, mush, and even bread (I myself love acorn bread). Excess unground, shelled acorns could be stored up to 10 years. The preparation of acorns was not just fulfilling a necessity. It was also a time for social connection during which the women could talk amongst themselves and share stories of their lives and even gossip.

“Acorn use by California Native Americans” by Kathleen McKeehen

https://www.science-art.com/image/?id=1841

The oaks were also vital to the Ohlone as markers for the changing of seasons. They were able to develop a sense of time by watching the changes in the oak trees such as the arrival of buds, flowers, and acorns as well as the loss of leaves in some species. This would tell them when animals, such as bears, would be coming to gather acorns and have their share of the feast.

In addition to food and a marker of time, the indigenous people of California made use of the oaks in many other ways. The tannins leached from acorns, as well as bark from the trees, could be used as a dye. The pigments were used to color animal skins, make ceremonial face paints, and even for tattooing. Tribes were known to use insect galls, leaves, and fungi growing on acorns for medicinal purposes such as cleaning wounds and stopping infections.

The Amah-Mutsun

https://slconservancy.org/inspire/native-american-culture/

Unfortunately, the arrival of the Spanish did not bode well for the native people nor the oaks of California. The Spanish introduced grazing animals and felled oak forests to make room for their agricultural enterprises. They also saw value in the lumber of oak trees, leading to even more deforestation. Before the native people could do anything to prevent them, the Spanish had dramatically damaged the relationship between the people and the oaks. Tribes like the Ohlone could no longer rely on the acorn as their primary food source and were forced to go to missions which actively discouraged and punished their traditional ways of living. Being forced into the Catholic way of living as a means to survive without their once plentiful native lands severely disrupted the Ohlone people and their connection to the land. Nowadays, many of their descendants view the oak tree and acorns as a reminder of their past and the traditional values that were stripped from their ancestors.

As time went on, the modernization and further settlement of California has pushed the oak trees into smaller and smaller areas. In 1994, sudden oak death caused by a fungus known as phytophthora ramorum (pronounced fai-toff-thor-ah rah-more-um) furthered the loss of oaks. An estimated one million oak trees have been lost to sudden oak death in California. The destruction of oak woodlands has threatened the lives of native Californian wildlife as well with more than 300 species dependent on them.

All hope is not lost, of course. Recent movements for urban forestry (like Our City Forest) and the restoration and protection of oak trees give hope to restoring the oaks in California that we all owe so much to. Additionally, the restoration of oaks serves to repay for the injustices faced by the native tribes of California and as a reminder of the people with the strongest connection to this land.

Part 3: A General Guide to Native Oaks of California

I want to preface this section with a disclaimer. As I mentioned before, there are some 600 species of oaks worldwide. This section only covers a few of those native to California, of which there are 20 species. The arrival of the Spanish and further settlement of California has introduced many other foreign species of oaks which you may run into around the Bay Area.

*The images are from Michael Lee’s illustrated poster of Native Oaks, the photos are from each species’ wikipedia page, and descriptions are from Pacific Coast Trees by Howard E. McMinn and Evelyn Maino

California Black Oak, Quercus kelloggii

Size: 30 to 80 feet tall

Range: Lower and middle mountain slopes and the foothills in the Coast Ranges and the Sierra Nevada to the mountains of southern California

Acorn: Cup covers ⅓ to ½ of the nut, rounded at the apex, 1 to 1 ½ inches long

Leaf: Lobed with 1 to 4 bristle-tipped teeth, 4 to 8 inches long, 2 ½ to 4 inches wide

Blue Oak, Quercus Douglasii

Size: 20 to 60 feet tall

Range: Lower dry mountain slopes and rocky foothills of the middle and inner Coast Ranges, the Sierra Nevada, and the Sierra Liebre

Acorn: Cup covers ¼ to ⅓ of the nut, variable in shape, commonly ovoid, ¾ to 1 ¼ inches long

Leaf: shallow lobes can also be ovoid, bluish green, 1 ½ to 4 inches long, ¾ to 2 inches wide

Canyon Live Oak, Quercus Chrysolepis

Size: 25 to 50 feet tall

Range: Mountain canyons and on moist ridges and flats of the Coast Ranges of southern Oregon and California, the lower and middle slopes of western Sierra Nevada and mountains of Southern California

Acorn: Shallow cup with thick walls, ovoid or oblong, 1 to 1 ¼ inches long

Leaf: Thick, leathery, elliptic-oblong or ovate, yellow underneath, spiny-toothed ¾ to 3 inches long, ½ to 1 ¾ inches wide

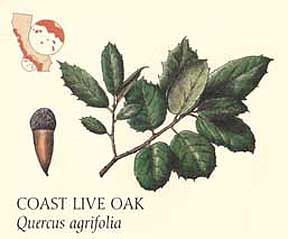

Coast Live Oak, Quercus Agrifolia

Size: 30 to 75 feet high

Range: Lower mountain slopes, rocky hills, and on valley flats of the Coast Ranges from Sonoma and Napa counties southward towards the mountains of southern California

Acorn: Cup covers ⅓ of the nut, slender and pointed, 1 to 1 ½ inches long

Leaf: Stiff, leathery, oval to almost round, glossy and pale beneath, spine tipped

Engelmann/Mesa Oak, Quercus engelmannii

Size: 20 to 50 feet high

Range: Foothills between the coast and the mountains of San Diego County

Acorn: Cup covers ¼ to ⅓ of the nut, ovoid, ¾ to 1 inch long

Leaf: Stiff, leathery, oblong to obovate, pale underneath, 1 to 3 inches long, ½ to 1 inch wide

Interior Live Oak, Quercus wislizenii

Size: 25 to 75 feet tall

Range: Lower mountain slopes and foothills of the Sierra Nevada from Kern County northward to Mount Shasta, southward in the Great Valley and Inner Coast Range

Acorn: Cup covers ¼ to ½ of the nut, oblong and pointed, 1 to 1½ inches long

Leaf: Stiff, leathery, oblong to ovate, glossy and dark above, pale underneath, 1 to 3 inches long, ¾ to 1 ¾ inches wide

Island Oak, Quercus Tomentella

Size: 20 to 40 feet tall

Range: Santa Catalina, San Clemente, Santa Cruz, Santa Rosa, and Guadalupe islands (not occurring on mainland)

Acorn: Cup covers ⅓ to ½ of nut, ovoid, rounded, ¾ to 1 ¼ inches long

Leaf: Thick and leathery, elliptic to oblong, dark green above, pale beneath, prominent veins, swollen teeth

Oregon White Oak, Quercus garryana

Size: 35 to 60 feet tall

Range: Coast Ranges of California to Marin County, Sierra Nevada to eastern Shasta County

Acorn: Shallow cup covers ⅓ of the nut, ovoid, rounded, ¾ to 1 inch long

Leaf: Wide, deeply 5- to 9-lobed, unequally toothed, dark green and glossy above, pale beneath, 3 to 4 inches long, 2 or 3 inches wide

Valley Oak, Quercus Lobata

Size: 40 to 125 feet high

Range: Sacramento, San Joaquin, and adjacent valleys, the foothills of the Sierra Nevada, inner and middle Coast Ranges south to San Fernando Valley

Acorn: Cup covers ¼ of the nut, long, slender, pointed, 1 ¼ to 2 inches long

Leaf: Broader towards apex, soft, green above, pale with yellow veins beneath, 7- to 11-lobed, 2 ½ to 4 inches long, 1 ½ to 3 inches wide

Part 4: Additional Information

Any sources I gathered information from are listed in the references at the end but I want to spotlight a few fascinating links and an acorn bread recipe to check out (acorns start to fall September to October)

The Ohlone and the Oak Woodlands: Cultural Adaptation in the Santa Clara Valley: https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/72850353.pdf

Past and Present Acorn Use in Native California:

https://sipnuuk.karuk.us/system/files/atoms/file/AFRIFoodSecurity_UCB_FrankLake_003_007.pdf

Books: Oaks of California by Bruce M. Pavlik, Secrets of the Oak Woodlands: Plants and Animals Among California’s Oaks by Kate Marianchild

Recipe for Acorn Bread http://ports.parks.ca.gov/?page_id=25519

References

“Home.” Rausser College of Natural Resources, UC Berkeley, nature.berkeley.edu/garbelottowp/?p=1749.

“Oak.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 22 June 2020, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Oak.

“Ohlone.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 25 June 2020, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ohlone#History.

“Re-Oak California.” California Native Plant Society, 11 June 2019, www.cnps.org/give/priority-initiatives/re-oak-california.

“Saving California's Oak Trees.” Sunset Magazine, 19 Mar. 2014, www.sunset.com/garden/flowers-plants/oak-tree.

“Sudden Oak Death.” Center for Invasive Species Research, 28 Dec. 2019, cisr.ucr.edu/invasive-species/sudden-oak-death#:~:text=It is estimated that the,of central and northern California.

“What Is Sudden Oak Death?” Sudden Oak Death, 2 Sept. 2017, www.suddenoakdeath.org/about-sudden-oak-death/.