Outside of our Urban Forestry Education Center at Martial Cottle Park is a shallow channel that borders our plot. At two points there are drains where run-off and stormwater enter and are directed to the bay. The water that manages to percolate into the soil enters the watershed by way of groundwater. There is a missing piece to this picture.

Impermeable surfaces like the asphalt walking paths next to this channel allow water to quickly run off and enter storm drains, redirecting water that could otherwise be put back into the watershed and restore groundwater levels. However, there are infrastructure solutions that can be easily installed, such as bioswales. For the past few months, we have been planning the installation of a bioswale outside of our Education Center and it will finally become a reality this Spring with help from the California Conservation Corps' Watershed Stewards Program!

What is a bioswale?

A bioswale, also called a bio-retention or biofiltration site, is a vegetated, sloped channel where large amounts of water flow are slowed and directed with purpose. This slowing allows the water to percolate into the soil to be filtered by the vegetation. This filtration removes excess nutrients, such as nitrates and phosphates, which can come from agricultural sources as well as urban fertilizer use. Abundant nutrients may sound like a positive, however excessive levels of nutrients result in a process known as eutrophication. High levels of nutrients result in the uncontrolled growth of plants and microorganisms such as algae. When these plants and microorganisms decay, the amount of bacteria needed to break them down consumes the dissolved oxygen in the water, creating what is often referred to as "dead zones'. These dead zones are stripped of dissolved oxygen which suffocates animals such as fish. Other contaminants such as metals and pesticides are also removed from the water by plants. Green infrastructure like bioswales helps protect and restore watersheds through this process of filtration and percolation.

Example of a California Native bioswale (Image source)

What is a watershed?

A watershed, also known as a drainage basin or catchment, is an area where rainfall and melted snow are channeled into groundwater, creeks, streams, and rivers where they eventually drain into estuaries, bays, and the ocean (NOAA). A watershed connects different ecosystems, including the urban environment, together from the highest mountain tops whose glacial peaks slowly melt down and travel through the landscape to the depths of the ocean. The paths of creeks and rivers are also critical habitat corridors that species such as salmon and terrestrial animals like bobcats and deer need to move their range and complete important points in their life cycle. In Santa Clara County, the Coyote Creek watershed (where our bioswale is located) includes key habitats that connect the Santa Cruz mountains to the Diablo Range. The riparian corridors created by the path of the creek and the habitats that it supports provide safe paths for our wildlife as well as food, water, and shelter.

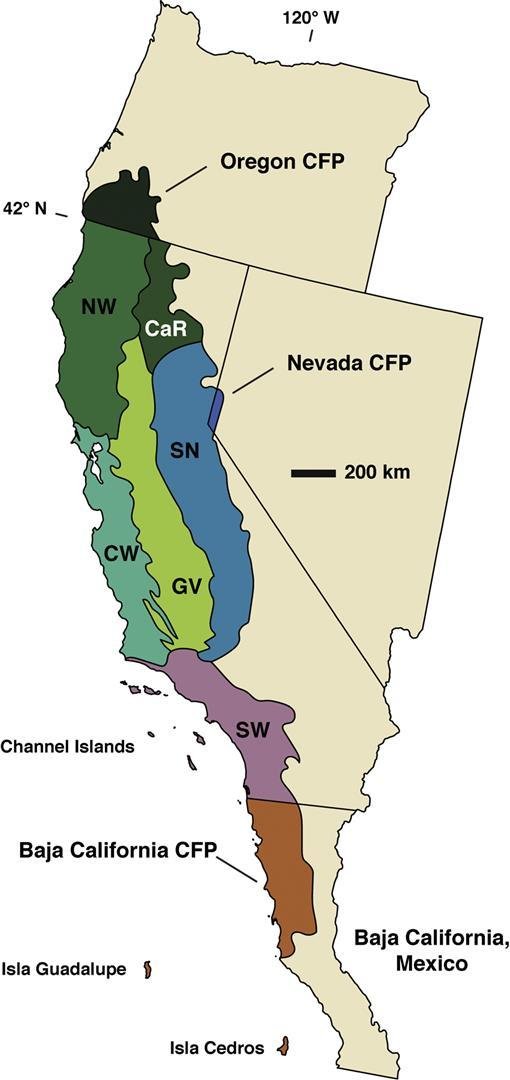

Watersheds of Santa Clara County. (image source)

The Watershed Stewards Program

As previously mentioned, our Bioswale project is a joint effort between Our City Forest and the Watershed Stewards Program (WSP) with plant donations made by local nurseries such as Grassroots Ecology. WSP is a program run by the California Conservation Corps (CCC) in partnership with Americorps. As stated by the CCC, WSP “is dedicated to improving watershed health by actively engaging in restoration science, civic service, and community education while empowering the next generation of environmental stewards". WSP corps members complete 11-month terms at placement sites such as government agencies, local organizations, and nonprofits to improve watershed health through a variety of methods like water quality monitoring, habitat restoration, and urban restoration projects like our bioswale.

WSP Corpsmembers Kalvin Joe, Katharine Major, and Emily Cox surveying a creek with WSP Mentor Eric Ettlinger. (Image source)

About Our Bioswale

On March 30th and April 6th, we will be installing our bioswale which is composed of over 200 plants across 22 California native species. The selection of these plant species is based on multiple factors. To start, we wanted this bioswale to be composed primarily of grasses and only native species. Unlike the grasses used in traditional lawns, many grasses native to California have vigorous, resilient, and long root systems which make them ideal for stabilizing slopes, preventing erosion, capturing water, and filtering out excess nutrients and pollutants. Many of these grasses are adaptable and can handle California's characteristic climate patterns of drought and flooding. Other factors in the species selection process included what species are resilient enough for the climate and soil at Martial Cottle Park, plants that support pollinators, aesthetics, and the availability of plants at our nursery as well as from the nurseries that have been so generous in their donations. Here is the complete list of species in our design:

Common Yarrow (Achillea millefolium)

Saltmarsh baccharis (Baccharis glutinosa)

Valley Sedge (Carex barbarae)

Foothill sedge (Carex tumulicola)

Soap Plant (Chlorogalum pomeridianum)

Sacred Datura (Datura writii)

Wild Rye Canyon Prince (Elymus condensatus ‘Canyon Prince’)

Creeping Wild Rye (Elymus triticoides)

Western Goldenrod (Euthamia occidentalis)

California Fescue (Festuca californica)

Creeping Red Fescue (Festuca rubra 'Pt. Molate')

Great Valley gumweed (Grindelia camporum)

Oregon gumweed (Grindelia stricta)

Common Rush (Juncus patens)

Deer Grass (Muhlenbergia rigens)

Marsh fleabane (Pluchea odorata)

Blue-eyed grass (Sisyrinchium bellum)

Yellow Eyed Grass (Sisyrinchium californicum)

Alkali Sacaton (Sporobolus airoides)

Purple needlegrass (Stipa pulchra)

California Aster (Symphyotrichum chilense)

California Grape (Vitis californica)

If you are interested in helping us plant our Native Bioswale, sign up for the first workday on March 30th and/or the second workday on April 6th. If you cannot make these dates don’t worry! Our new bioswale will have plenty of weeding, watering, and educational workdays in the coming future and possibly even an extension along our southern gate!

Common Yarrow (Achillea millefolium). (Image source)

Deer Grass (Muhlenbergia rigens). (Image source)

Wild Rye Canyon Prince (Elymus condensatus ‘Canyon Prince’). (Image source)

Western Goldenrod (Euthamia occidentalis). (Image source)

Sacred Datura (Datura writii). (Image source)